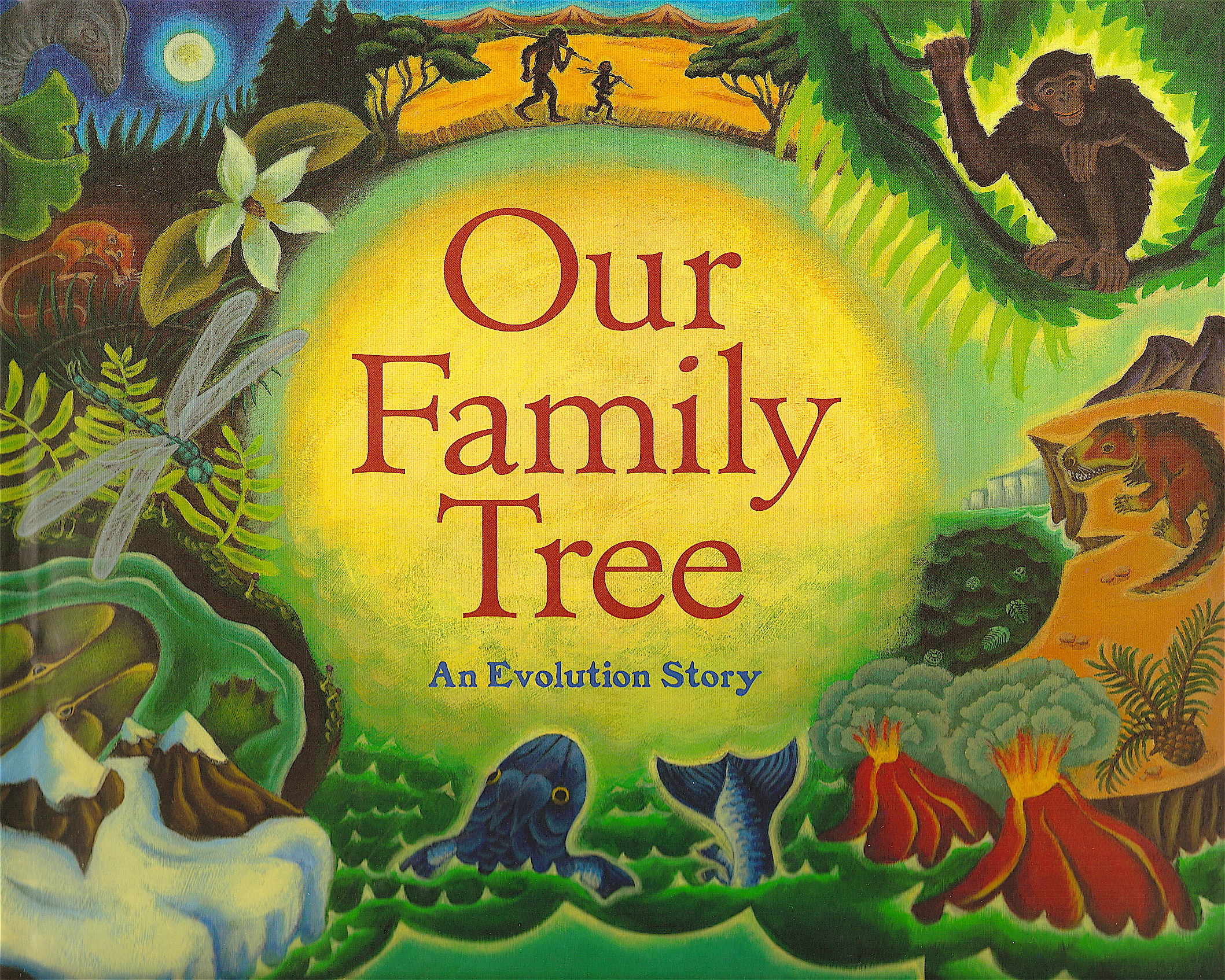

Our Family Tree: An Evolution Story

All of us are part of an old, old family. The roots of our family tree reach back millions of years to the beginning of life on earth. Open this family album and embark on an amazing journey. You’ll meet some of our oldest relatives—from both the land and the sea—and discover what we inherited from each of them along the many steps of our wondrous past.

Complete with an illustrated time line and glossary, here is the story of human evolution as it’s never been told before

Lisa Westberg Peters, illus. Lauren Stringer

Harcourt Children’s Books, April 2003.

48 pages, all ages. ISBN: 0152017720

This book appears on a Banned/Challenged Book List.

Awards & Recognition:

2004 Riverbank Review Book of Distinction

2004 Minnesota Book Award Winner

2004 PEN Center USA Literary Award finalist

Click here for Our Family Tree reader activities.

The Story Behind the Story

Open this family album and embark on an amazing journey. You’ll meet some of our oldest relatives–from both the land and the sea–and discover what we inherited from each of them along the many steps of our wondrous past.

On TeachingBooks.net, you can hear me talk about how I came to write Our Family Tree and why I think the book is important.

It took me years to write Our Family Tree. It won’t take you nearly that long to read this article from the Riverbank Review, which describes my writing and thinking process.

The Evolution of Our Family Tree

By Lisa Westberg Peters

Riverbank Review, Spring 2003

It took me about thirteen years—and forty-five minutes—to write Our Family Tree, a book that traces the lineage of humans back to the earliest life on earth.

I didn’t set out to write this book. It would be more accurate to say that I watched my two daughters grow up; hauled them on rock-collecting trips out West; discovered a fascination with evolution; rediscovered a childhood interest in geology; and read a stack of books about both. Finally, my thoughts acquired enough substance to slide from my pen, like snow from a branch.

My writing journey started in a tent in the mountains of eastern Washington.Seattle residents at the time, my husband and I had left our young daughters in the care of friends to go backpacking in a beautiful area called the Okanogan. At night, Dave read to me from a collection of natural history essays by Stephen Jay Gould. I was immediately struck by Gould’s astonishing view of the world.

Gould suggests that human evolution was not inevitable—in fact, not even probable. He maintains that single-celled life has been the most successful form of life on earth. His suggestions demand a more humble, less arrogant way of looking at ourselves. And yet, we are the creatures who have been painting spectacular art on ceilings for at least 17,000 years—from the prehistoric paintings of animals and mythical creatures that practically leap from the rocks of caves, to the more recent Michelangelo masterpiece of God reaching out to Adam, a breathtaking scene in the Sistine Chapel that leaves no visitor unmoved.

I wanted to write about evolution. I knew that this subject pulled on my emotions and made me wonder what it means to be human. Whatever I wrote, I wanted to make room for that emotion and that sense of wonder. As my daughters entered school, I looked for children’s books on the subject and found precious few. Sara Stein’s The Evolution Book (Workman, 1986) stood out, offering the full sweep of earth and life history in engaging, clear, and accessible prose. When my girls became enthusiastic, independent readers, I scribbled down several proposals for children’s nonfiction books, the kind that school librarians want and need for eight-to-twelve-year-olds. But in the end, the proposals didn’t have the right shape for me. They didn’t allow for what Barbara Kingsolver has called “the poetry that camps outside the halls of science.”

I put aside my proposals and tried to learn all I could on the subject of evolution. Scientists Niles Eldredge and David M. Raup got me thinking about the role of chance and extinction in evolution. In Edward O. Wilson’s book The Diversity of Life, this prominent biologist states that human activity is degrading ecosystems, reducing biodiversity and causing another mass extinction today. In The Third Chimpanzee, Jared Diamond taught me that we share an astonishing 98 percent of our genes with these primates, who are our closest relatives.

One of my daughters, soon to become a biology major in college, lent me her high school science textbook, and I read about the intricacies of evolutionary biology. For a while, I thought I could write about evolution by focusing on oysters. I had found ancient oyster fossils at the top of a mountain and I had plucked them fresh out of Puget Sound. This made me wonder how oysters had changed over the eons. My curiosity led me into dark and scary library stacks where I sat in narrow aisles lighted by a few bare bulbs, scanning the pages of such books as Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. But the oyster idea never took off.

My journalist husband told me about an upcoming conference of biology teachers, and I got myself a media pass to attend. At this conference I was reminded of the fact that most Americans either don’t understand or don’t accept the idea of biological evolution. A recent National Science Foundation survey showed that less than half of the American population understands that humans evolved from earlier species of animals. The fact that evolution is completely ignored in many schools can be seen as both a consequence and a cause of this situation. Despite the fact that mainstream Judaism and Christianity—and the pope himself—accept biological evolution, many teachers are still afraid to teach the idea that life has changed over time.

As I was discovering evolution, I rediscovered geology, a childhood interest that had lain dormant in the whirl of starting a career, settling into marriage, and rearing children. I decided to take some geology classes at a community college. A thirtysomething mother, I went on field trips with twenty-something kids on Washington’s soggy coast. I looked for garnets in the shiny schists of the Cascade Mountains. I took photos of jagged rocks and

beach pebbles, photos that still hang on my walls.

After we moved back to our native Minnesota, I set aside Monday nights for lectures sponsored by a geological society and listened to an anthropologist describe brain size in terms of beer cans. (We have a four-beer-can brain; chimps have a one-beer-can brain.) My early mornings were devoted to a radio program called Earth and Sky, though I wasn’t always awake for these perky scientific tidbits.

As with evolution, the more I learned about geology, the more I wanted to write about it for children. In this case, I found a satisfying form fairly quickly. The Sun, the Wind and the Rain, my first children’s picture book, is a story about change, a force that is both constant and inevitable, even for something as huge as mountains.

Gradually I found myself drawn to the change that occurs when evolution and geology intersect. We owe our own presence on earth to such an intersection. When an asteroid hit the earth 65 million years ago, the dinosaurs fizzled out and in the empty niche, mammalian evolution took off. We humans are one result of mammalian evolution. This intimate connection between life and earth seems especially relevant today. A recent New York Times headline read, “Warming Is Found to Disrupt Species: Range and Habits Are Shifting, Climate Scientists Report.” A changing planet is apparently changing the course of life. Or is it the other way around? Is life changing the planet? And what is our role in those changes?

The idea for Our Family Tree: An Evolution Story finally came to me in part out of frustration. I had never seen a book—for children or adults—in which our distant cousins in the fossil record were conveniently lined up and labeled as relatives. I realized I could do that. This family album approach provided the frame of reference I was looking for, since children often see family albums at home or make family trees at school. My story would extend the concept of family to include ancestors that all of us have in common, ancestors that go back more than 3 billion years. Central to the story would be its environmental context: the changing earth. I not only wanted to show my readers that we are connected to all of life, but that we are connected to the planet as well.

Despite having found a familiar frame of reference, I knew I would be entering territory foreign to most children. I wanted to try to engage readers by writing a clear and simple story, not a list of facts. As a picture book writer, I also needed to write a story that offered plenty of visual opportunities and inspiration to an artist, because the images would play a critical role in introducing this subject to children.

I sat on my back porch surrounded by a struggling Minnesota spring. After thirteen years of reading, scribbling, searching, and listening—acquiring an education—it took less than an hour to write the manuscript that was to become Our Family Tree. When I was finished, I knew it was the story I wanted to tell.

My story starts with the words “All of us are part of an old, old family. The roots of our family tree reach way back to the beginning of life on earth. We’ve changed a lot since then.” Children will discover that we inherited such things as DNA from the earliest life, backbones from early fish, and fingernails from early primates—all this while the continents were drifting and the seas were rising and falling. I didn’t want to use words like “primate” or “extinction” or even “evolution” in a poetic text; I trusted that art would help bring the story’s concepts and creatures to life.

In my story, I used the first-person voice deliberately. I hoped it would help children identify with the odd creatures that would play starring roles. I was aware that the word we might be provocative for those who reject the idea that humans evolved from earlier species of animals. But I consider it the most comforting word in the story. It’s the word that reminds me we’re not alone. We have three and a half billion years’ worth of ancestors, and today, we are surrounded by cousins, some distant, some close.

As members of this old, old family, we may not be able to predict our ultimate fate — evolution is unpredictable. But we are able to make some choices that will affect the quality of our lives and the lives of our daughters and sons. We can protect ecosystems or we can watch them vanish. We can consume fewer resources or we can increase our consumption. A stronger sense of belonging to the natural world might help to inform the choices that we make about “where we’re going next,” which is the question my book poses to its readers.

—Lisa Westberg Peters

Reviews

Kirkus Reviews

Luminous, eye-filling paintings accompany a poetic disquisition on our ancestors, from primordial single-celled creatures to dexterous, big-brained walkers. Framing the discourse with scenes of an adult drawing linked pictures in the sand for two children, Stringer (Mud, 2001, etc.) gives her dramatically posed prehistoric figures even more visual impact by outlining them in light, and placing them against vivid, undulant sea- or landscapes. Beginning with the appearance of multi-celled organisms, Peters (Cold Little Duck, Duck, Duck, 2000, etc.) traces successive developmental watersheds, including the appearance of backbones, lungs, warm blood, milk, and finally hands, through two major mass extinctions and up the present—then appends more detailed recapitulations of each stage in glosses and a separate time line. Source notes from author and illustrator cap a lyrical, carefully researched look into our deep past that will give young readers a firm sense of their place within the long history of life on this planet.

Copyright © 2003, Kirkus Reviews

School Library Journal

“All of us,” (Peters) states in the first sentence of the book, “are part of an old, old family,” going back to Earth’s beginnings. “We’ve changed a lot since then.” Through a simple progression, amply bolstered by Stringer’s striking, large acrylics, she traces “our” family tree from unicellular organisms through amphibians, therapsids, and early mammals to early primates, hominids, and our distinct “humanness” today. Enriched by two pages of additional data and a colorful time line, the whole is rounded out by carefully written author and illustrator notes.

Copyright 2003, School Library Journal